On April 5, gain clarity on how Biglaw fits into your broader career vision, whether you plan to stay for 3 months or 30 years. (Register by April 3.)

In a world where BigLaw faces a steady stream of criticism, and critics propose too few solutions, a union movement deserves serious consideration.

One goal of this discussion is to encourage future and new attorneys not to undersell their ability to assert their rights within their own profession. If they cannot do it, then who can?

This is part one of a two-part article. Part one examines the potential formation of a BigLaw associate union, with a practical focus on how recent recruiting trends and student activism are poised to catalyze change. Part two will explore how a BigLaw union could address an array of issues beyond recruiting, including attorney well-being.

Some commentators have expressed skepticism about the idea of a BigLaw associate union, despite acknowledging that there are no apparent legal obstacles.[1] In fact, Boston firm Segal Roitman LLP and plaintiffs firm Outten & Golden LLP each voluntarily recognized unions of their associates in 2022 and 2023, respectively.[2]

While these firms are small compared to the BigLaw giants, the recent so called precruiting trend presents a far-reaching issue for law students and associates to rally around. The precruiting trend demonstrates BigLaw firms' view that the law student talent pool is of paramount importance. It therefore also highlights:

- The underestimated leverage that law students have to influence BigLaw policies;

- Potential tactics that are, notably, protected under the National Labor Relations Act; and

- An avenue for student activism to lay the groundwork for associate unionization.

Skeptics cite high pay, competitiveness and high associate turnover as barriers to BigLaw associates' motivation to unionize, but a study conducted by Major Lindsey & Africa and Leopard Solutions, published in April, suggests that Generation Z sentiments on issues like pay and ultimate career goals are changing.

Additionally, multiemployer bargaining — similar to what we see in sports leagues such as the NBA — could create cohesion and consistency across BigLaw firms.[3]

In this context, unionization remains a promising path forward for those who not only identify challenges, but are also driven to forge solutions.

Why the Time Is Ripe for a BigLaw Union Movement

In the last couple years since on-campus interviews returned in-person to law schools, BigLaw firms have begun interviewing students for 2L summer jobs earlier and earlier.[4] For years prior to the pandemic, law schools and BigLaw firms would coordinate to host OCI for law students after the completion of their 1L year, most recently in the late summer prior to the start of their 2L year.[5]

Now, the process has sprawled into an increasingly complex and unpredictable situation referred to as pre-OCI, direct hiring, or precruiting, with BigLaw firms opening applications, interviewing, and making offers to students prior to the end of their 1L spring semester, sometimes as early as February.[6][7]

Some firms are requiring students to make decisions on pre-OCI offers before the end of OCI, sometimes in as little as two weeks.[8]

The director of attorney recruiting at Morrison Foerster LLP, which participated in precruiting this year, noted that this process was likely to fill at least half of the firm's summer class, adding that the firm feels that waiting for traditional OCI would cause it to miss out on talent that's scooped up pre-OCI by other firms.[9]

This year, Morrison Foerster reportedly opened applications in May, along with Milbank LLP, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, Paul Hastings LLP and Sidley Austin LLP, and Jones Day and Weil Gotshal & Manges LLP reportedly opened applications in April.[10]

Precruiting has received significant criticism. The dean of Georgetown University Law Center and the assistant dean of its Office of Career Strategy recently weighed in on the trend, describing it as a "race to the bottom [that] is harmful to everyone involved."[11]

Their criticisms include the overlapping pressures students feel to apply and interview for 2L summer jobs while they are still acclimating to the first year of law school; preparing for exams; applying to or juggling the demands of 1L summer jobs, sometimes at competitor firms; and just beginning to consider the types of careers they want to pursue.[12]

Others have noted the disproportionate impact on first-generation students, who are more likely to come from diverse backgrounds, emphasizing the knowledge gap about how the system operates and about BigLaw culture in general.[13]

Landing offers for BigLaw 2L summer positions and choosing a firm are significant career milestones, considering the expectation that these jobs lead to full-time offers and, at a minimum, are a pivotal data point on candidates' resumes.[14]

Why Precruiting Is Happening Now

Prior to 2018, the National Association for Law Placement had played a critical role in BigLaw firms' willingness to coordinate the 2L summer recruiting process with law schools.[15] NALP had issued guidance that, among other things, set out timing guidelines for formal applications, offers and interviews between 1Ls and prospective employers, and recommended a 28-day minimum period for which offers should remain open.[16]

Then, in late 2018, NALP announced that it had made sweeping changes to that guidance, including the elimination of the concrete timing guidelines.[17]

Granted, the NALP guidance was never binding on BigLaw firms, and the 2019 recruiting landscape doesn't appear to have reacted much to the change. But the seismic shifts seen in the last few years appear to have been catalyzed by (1) the pandemic, which necessitated changes in 2020, and (2) the evolving sentiments reflected in the 2018 revisions to the NALP guidance.

Though it wasn't cited as a reason at the time,[18] it appears that antitrust concerns were a motivator for the 2018 NALP changes. In 2023, NALP issued this statement:

"NALP recognizes that pre-OCI recruiting can create challenges for our school members[, students] and … our employer members ... We have determined, however, that we cannot provide unilateral direction on this issue ... Trade association policies related to how members compete with one another, including how they compete for talent, can potentially raise antitrust issues. ... [G]iven these risks, NALP must refrain from providing guidance on these issues. We would also caution members that working among themselves to try to limit pre-OCI recruiting activities could similarly raise antitrust risks."[19]

The upshot is that there are antitrust barriers to BigLaw firms coordinating the timing of recruiting milestones, whether that's through NALP, the law schools or among themselves.

With competitors interviewing earlier and earlier, BigLaw decision-makers may feel that their hands are tied, even if some quietly believe that an organized process would benefit everyone.

Collective Bargaining as a Legal Avenue to a Uniform BigLaw Recruiting Process

Despite feeling powerless in the precruiting process, law students themselves hold the potential solution to this tension through the labor exemption to antitrust liability, which consists of two parts.

The statutory exemption generally shields labor (e.g., union-related) activity from antitrust liability,[20] and the nonstatutory exemption generally protects the broader collective bargaining process.[21]

Very generally, this means that behavior that would otherwise be deemed anticompetitive, such as agreements among BigLaw firms restricting how they compete for law student hires — by, e.g., fixing consistent dates for applications and offers — is exempted from antitrust liability if it is done in connection with legitimate union activity, e.g., firms coming to an agreement with an associate union on such fixed dates.

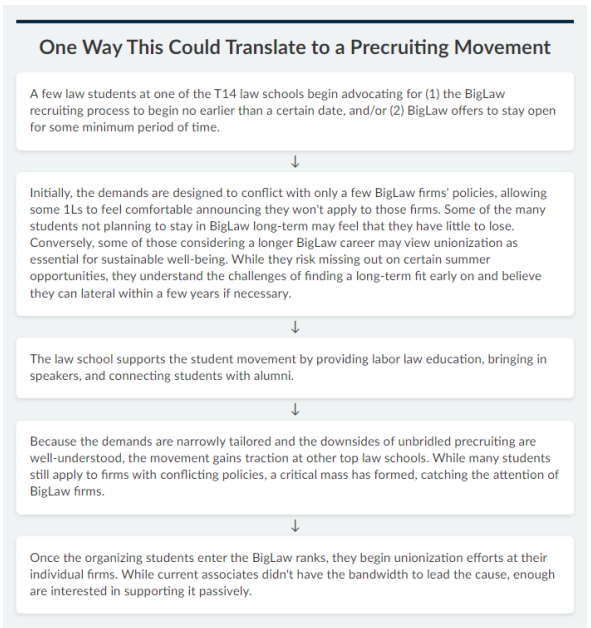

While 1L recruits are not yet employees and therefore cannot unionize, they can engage in awareness-raising activities, gather resources and plan strategically, all while building social solidarity and establishing leadership around the pertinent issues.

Once these organizing students graduate and join the associate ranks, they can parlay that groundwork into formal unionization efforts at their individual BigLaw firms.

And, once a union at any given firm is either voluntarily recognized or elected following a petition with the National Labor Relations Board, this obligates the firm to collectively bargain with the union as the representative of the associates with respect to mandatory subjects, which generally include wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment.[22]

To negotiate uniform policies, the unions and the BigLaw firms could explore the possibility of multiemployer bargaining. If the firms and the unions agree, the BigLaw firms would form a multiemployer bargaining unit, and the single-firm unions would combine.[23]

An example of how multiemployer bargaining works in practice is the collective bargaining agreement between the NBA and the NBA players' union, the National Basketball Players Association Inc., since each NBA team is a separate employer.

Their collective bargaining agreement includes procedures for the college player draft — i.e., the rules, including timing, for how new hires are made — as well as rules about compensation, such as salary minimums and maximums; benefits; and procedures, including players' rights, when players are subject to discipline for either on-court or off court conduct.[24]

Since law school recruiting policies are terms and conditions of employment — analogous to the NBA draft — and therefore a mandatory subject, multiemployer bargaining with associates to reach a single collective bargaining agreement provides a pathway for BigLaw firms to legally collaborate on consistent policies around law school recruiting timelines without violating antitrust laws.

Why a Law Student Movement Is a Promising Path to a BigLaw Union

Law schools are fertile ground for a student movement that could ultimately evolve into the cohesive group of associates needed to form a BigLaw union.

In contrast to the BigLaw environment, the law school environment is conducive to activism due to students' greater idealism and more predictable schedules, together with the willingness of deans, professors, and other law school personnel to provide education, support, and resources for student causes.

Many law school personnel have been vocal in their criticisms of precruiting. But while some BigLaw attorneys may share those sentiments, they may understandably be hesitant to express concerns publicly.

Law students and early-career associates may fear retaliation from BigLaw firms because of their demands for change. The good news is that the NLRA generally protects law students and associates from discriminatory hiring and employment practices relating to their engagement in labor movements.[25]

This means, among other things, that it would be illegal for firms to withhold offers of employment or terminate associates based on union advocacy. More specifically, the NLRA generally protects applicants and employees from discrimination for demanding changes with respect to mandatory subjects of collective bargaining — which would include law school recruiting policies — even without union status, efforts or discussions.[26]

Students' and associates' speech and activities criticizing precruiting practices would therefore be legally protected regardless of future union membership.[27]

Despite the NLRA's protections, there is always the concern that employment decisions may be framed in terms that appear legal, making it challenging to prove any wrongdoing. But law students have advantages here. There is strength in numbers, and law students can assemble more quickly than associates. It would quickly become apparent that firms were engaging in illegal anti-labor activity if they were to withhold offers from student organizers en masse.

It's also much harder to argue that students, even as summer associates, are neglecting firm duties as compared to full-time associates, thereby mitigating an easy pretext for targeting them. And students' efforts during law school would result in a less time-intensive path to unionization once they start full-time.

Law students also have a unique and often overlooked leverage. Because BigLaw firms must continuously hire junior associates to, among other things, offset high attrition rates, summer associate hires are the lifeblood that sustains BigLaw.

While law students, due to their lack of experience, are theoretically more replaceable, BigLaw firms must carefully manage their reputations within law schools, as negative perceptions can spread quickly and hinder a firm's ability to attract top talent.

This counterintuitive dynamic gives law students more influence over BigLaw policies than current associates and, arguably, even some partners.

Finally, law students are more uniformly positioned than associates, giving them more common ground for solidarity. Precruiting has concrete and immediate repercussions that are nearly universal for students at top law schools, providing a tangible cause to unite around.

As these students transition to associate roles, the foundations and networks they build during law school provide them with the tools and unity necessary to translate their efforts into unionization before they are too deep into the survival mode characteristic of the first year of practice.

The hope is that these associates would continue their advocacy not only to establish reasonable recruiting policies for their more junior classmates, but also to improve their own BigLaw working conditions.

By contrast, as associates become more integrated into their practice groups, their challenges become more varied, complacency and burnout become more likely, and their leverage diminishes.

That's why a union movement that originates in law schools not only capitalizes on a supportive environment and fewer barriers, but also on a strategic window of opportunity that narrows with time.

Recent History of Law Student BigLaw Activism

How does this hypothetical union put down its roots in law schools? History tells us that it's not as far-fetched as it may initially appear.

In 2018, two Harvard Law School students founded the Pipeline Parity Project, or PPP, now known as the People's Parity Project.

The movement was inspired by a Harvard Law School lecturer, who leaked an employment policy from Munger Tolles & Olson LLP, which, at the time, subjected summer associates to mandatory arbitration clauses, including with respect to sexual harassment claims.[28]

Within days of the leak, and on the heels of the #MeToo movement, Munger Tolles announced it would no longer require its employees, including summer associates, to sign mandatory arbitration agreements, and other BigLaw firms made similar announcements.[29]

Shortly after, a group of Harvard law students wrote an open letter asking the school to, among other things, require firms that recruit on campus to remove mandatory arbitration clauses from their employment agreements.[30]

In response, dozens of top law schools, including Harvard, Yale Law School and Stanford Law School, announced that they would require firms that recruit on campus to disclose whether they require summer associates to sign mandatory arbitration agreements, sending a survey to 374 firms.[31]

The fact that nearly half the firms declined to answer appears to have only emboldened the students.[32] By late 2018, over two dozen Harvard law students were active PPP members, and hundreds had joined its email list.

PPP encouraged Harvard law students to boycott interviewing with Kirkland & Ellis LLP until the firm removed mandatory arbitration from all employee agreements.[33] Shortly after, Kirkland announced that it would remove mandatory arbitration agreements for associates, including summers, and then announced that it would remove them for all its employees.[34]

PPP later directed a boycott at DLA Piper,[35] and is now a national organization with student chapters at other top law schools, as well as attorney chapters in major cities.[36]

Conclusion

Skeptics might argue that a law school union movement would struggle due to lack of student interest, but the PPP story demonstrates that only small numbers may be required to spark change, and that many law students are indeed willing to support a movement seeking to change BigLaw policies.

While addressing precruiting is commendable, numerous other issues — both present and future, known and unknown — necessitate ongoing advocacy.

Layoffs, political speech, return to office, well-being, promotion to partnership and AI are just a few of the topics that will be explored in part two of this article.

Copyright © 2024 Tara Rhoades

All rights reserved.

Tara Rhoades is the founder at The Sanity Plea LLC. She is a former associate at Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP, and a former partner at Kirkland & Ellis.

[1] "Unionizing Big Law Associates Is Tough Sell in Competitive World," Bloomberg Law (August 7, 2023), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/unionizing-big-law associates-is-tough-sell-in-competitive-world.

[2] "Unionizing Big Law Associates Is Tough Sell in Competitive World," Bloomberg Law (August 7, 2023), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/unionizing-big-law associates-is-tough-sell-in-competitive-world.

[3] Incidentally, The New York Times also recently drew parallels between BigLaw and the NBA (albeit in the context of equity partner compensation), arguably making this comparison all the more pertinent. "Pay for Lawyers Is So High People Are Comparing It to the N.B.A.," The New York Times (published July 1, 2024 and updated July 2, 2024), https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/01/business/law-firm-pay-salary.html.

[4] "Big Law Skips Ahead of On-Campus Recruiting in Talent Race (1)," Bloomberg Law (published and updated April 22, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and practice/big-law-skips-ahead-of-on-campus-recruiting-in-race-for-talent.

[5] "Early Big Law Recruiting Is Ruining the First Year of Law School," Bloomberg Law (May 16, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/early-big-law-recruiting-is-ruining the-first-year-of-law-school.

[6] "Early Big Law Recruiting Is Ruining the First Year of Law School," Bloomberg Law (May 16, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/early-big-law-recruiting-is-ruining the-first-year-of-law-school.

[7] "Big Law Skips Ahead of On-Campus Recruiting in Talent Race (1)," Bloomberg Law (published and updated April 22, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and practice/big-law-skips-ahead-of-on-campus-recruiting-in-race-for-talent.

[8] "Big Law Skips Ahead of On-Campus Recruiting in Talent Race (1)," Bloomberg Law (published and updated April 22, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and practice/big-law-skips-ahead-of-on-campus-recruiting-in-race-for-talent.

[9] "Big Law Skips Ahead of On-Campus Recruiting in Talent Race (1)," Bloomberg Law (published and updated April 22, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and practice/big-law-skips-ahead-of-on-campus-recruiting-in-race-for-talent.

[10] "Big Law Skips Ahead of On-Campus Recruiting in Talent Race (1)," Bloomberg Law (published and updated April 22, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and practice/big-law-skips-ahead-of-on-campus-recruiting-in-race-for-talent.

[11] "Early Big Law Recruiting Is Ruining the First Year of Law School," Bloomberg Law (May 16, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/early-big-law-recruiting-is-ruining-the-first-year-of-law-school.

[12] "Early Big Law Recruiting Is Ruining the First Year of Law School," Bloomberg Law (May 16, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/early-big-law-recruiting-is-ruining the-first-year-of-law-school.

[13] "Big Law Recruiting Rush Puts More Pressure on Diverse Students," Bloomberg Law (May 13, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/big-law-recruiting rush-puts-more-pressure-on-diverse-students.

[14] "Big Law Recruiting Rush Puts More Pressure on Diverse Students," Bloomberg Law (May 13, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/big-law-recruiting rush-puts-more-pressure-on-diverse-students.

[15] "Big Law Skips Ahead of On-Campus Recruiting in Talent Race (1)," Bloomberg Law (published and updated April 22, 2024) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and practice/big-law-skips-ahead-of-on-campus-recruiting-in-race-for-talent.

[16] Prior to the 2018 changes, NALP's guidance was known as "NALP's Principles and Standards for Law Placement and Recruitment Activities." See "NALP Principles for a Fair and Ethical Recruitment Process" (December 12, 2018),https://www.nalp.org/uploads/PFERP/NALPPrinciples_MemotoMbrs.pdf.

[17] "NALP Principles for a Fair and Ethical Recruitment Process" (December 12, 2018), https://www.nalp.org/uploads/PFERP/NALPPrinciples_MemotoMbrs.pdf.

[18] The reasons for the 2018 changes cited in the NALP announcement included member organizations having "grown past 'one size fits all' standards" and a belief that "encourag[ing] broader experimentation provides a path to meaningful positive change in entry-level recruiting." See "NALP Principles for a Fair and Ethical Recruitment Process" (December 12, 2018), https://www.nalp.org/uploads/PFERP/NALPPrinciples_MemotoMbrs.pdf.

[19] "Open Letter to Members on Pre-OCI Recruiting" (February 28, 2023), https://www.nalp.org/open_letter_on_pre-oci_recruiting. This wasn't the first time that NALP appears to have acted (or declined to act) in response to antitrust concerns. In 2010, NALP had considered releasing guidance that employers should not make offers for 2L summer jobs until January of the students' 2L year (about 5 months after the then-typical August OCI period) in order to address some NALP members' concerns about the pressure to interview as early as possible, the limited time window to assess candidates, and the prospect of firms making hiring decisions without seeing year-end financials. (See "NALP Group Recommends Jan. Job Offer Kick-Off Day," ABA Journal (January 8, 2010), https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/nalp_group_recommends_jan._job_offer_ kick-off_day.) Some firms opposed the proposal as making recruiting more costly and difficult, while others welcomed the proposed change. (See https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/big_ny_firms_resist_nalp_proposal_to_dela y_job_offer_date and https://amlawdaily.typepad.com/amlawdaily/2010/02/nalpdebate.ht ml.) Notably, Jones Day had raised the possibility that the proposal would violate antitrust rules. (See https://amlawdaily.typepad.com/amlawdaily/2010/02/nalpdebate.html.) Ultimately, NALP abandoned the proposed changes.

[20] This protection applies provided that a labor organization (1) acts in its own self interest and (2) is not working in concert with non-labor organizations. See Section 6 of the Clayton Act (15 U.S.C. § 17) and U.S. v. Hutcheson, 312 U.S. 219 (1941).

[21] This protection applies provided that (1) any resulting restraint on trade primarily impacts the parties to the collective bargaining relationship, (2) the subject of the bargaining is a "mandatory" subject, and (3) the bargaining is bona fide and arm's length. For summaries of the extensive case law on the non-statutory exemption, see Hynes, Eleanor M. "Unnecessary Roughness: Clarett v. NFL Blitzes the College Draft and Exemplifies Why Antitrust Law is also 'A Game of Inches,'" J. of Civil Rights and Econ. Dev., Vol. 19, Issue 3 (Summer 2005) and "Nonstatutory Labor Antitrust Exemption Risk In Sports Unions," Law360 (December 5, 2022), https://www.law360.com/articles/1552027/nonstatutory-labor-antitrust-exemption risk-in-sports-unions.

[22] National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), 29 U.S.C. § 158(d).

[23] For more information about the process of forming a union and multi-employer bargaining, see https://www.nlrb.gov/about-nlrb/rights-we-protect/the law/employees/your-right-to-form-a-union and https://www.epi.org/publication/collective-bargaining-beyond-the-worksite-how-workers-and-their-unions-build-power-and-set-standards-for-their-industries.

[24] 2023 NBA-NBPA Collective Bargaining Agreement (Effective as of 7/1/2023), https://www.nbpa.com/cba.

[25] Section 8(a)(3) of the NLRA, 29 U.S.C. § 158(a)(3). The NLRB website interprets this to prohibit employers from refusing to "hire or consider job applicants because of their union membership, activities, or sympathies." (https://www.nlrb.gov/about-nlrb/rights-we-protect/the-law/discriminating-against-employees-because-of-their-union).

[26] Section 7 of the NLRA (29 U.S.C. § 157) gives employees (and where relevant, prospective employees) the right not only "to form, join, or assist" broadly defined "labor organizations" (defined in NLRA, 29 U.S.C. § 152(5)), but also "to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection," so long as the concerted activities (generally meaning "group" activities, see, e.g., Meyers Indus., Inc., 281 N.L.R.B. 882 (1986)) are reasonably related to wages, hours, or other terms and conditions of employment (see, e.g., Eastex, Inc. v. NLRB, 437 U.S. 556 (1978)) and are done by "permissible means" (see NLRB v. Local Union No. 1129, IBEW (Jefferson Standard), 346 U.S. 464 (1953), where employees' speech disparaging the employer's products was unprotected). See, e.g., Three D, LLC v. Nat'l Labor Relations Bd., 629 F. App'x 33 (2d Cir. 2015) for an example where employees' activities were protected even in the absence of union activity or discussions. Section 8(a)(1) of the NLRA (29 U.S.C. § 158(a)(1)) makes it an unfair labor practice for an employer "to interfere with, restrain, or coerce employees in the exercise of" their Section 7 rights. The courts have interpreted Section 8(a)(1) violations to include not only threats against employees, but also conduct that is favorable to employees if the conduct is intended to influence employees against exercise of their Section 7 rights. See Labor Board v. Exchange Parts Co., 375 U.S. 405 (1964) ("We have no doubt that [Section 8(a)(1) of the NLRA] prohibits not only intrusive threats and promises, but also conduct immediately favorable to employees which is undertaken with the express purpose of impinging upon their freedom of choice for or against unionization and is reasonably calculated to have that effect."). Part two of this two-part article will delve deeper into the boundaries of these protections.

[27] Just this month, the United Auto Workers Union filed charges with the NLRB against Donald Trump and Elon Musk, alleging that their recent conversation about firing non-unionized Telsa employees for going on strike illegally threatens and intimidates employees in the exercise of their rights under the NLRA. See "UAW files federal labor charges against Donald Trump and Elon Musk after threatening workers on X interview," CNN (August 13, 2024) https://www.cnn.com/2024/08/13/business/uaw-trump-musk-charges/index.html.

[28] "Law Students Raise Concerns About Firms' Summer Agreements," The Harvard Crimson (April 20, 2018), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/4/20/law-firms-nda me-too.

[29] Around the same time, Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP made a similar announcement, and days later, Law360 reported that Skadden Arps Slate Meagher & Flom LLP had also made a similar announcement in an internal communication.

[30] "Law Students Raise Concerns About Firms' Summer Agreements," The Harvard Crimson (April 20, 2018), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/4/20/law-firms-nda me-too.

[31] "Harvard Law Students Push Major Firm to Drop Controversial Contract Provisions," The Harvard Crimson (November 26, 2018), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/11/26/kirkland-ellis-boycott/.

[32] "Harvard Law Students Push Major Firm to Drop Controversial Contract Provisions," The Harvard Crimson (November 26, 2018), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/11/26/kirkland-ellis-boycott/.

[33] "Harvard Law Students Push Major Firm to Drop Controversial Contract Provisions," The Harvard Crimson (November 26, 2018), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/11/26/kirkland-ellis-boycott/.

[34] "Harvard Law School Pipeline Parity Project Celebrates Another Change to Controversial Law Firm Policies," The Harvard Crimson (December 10, 2018), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/12/10/pipeline-parity/.

[35] "Women's Law Associations Condemn Controversial Agreements, Praise Harvard's Pipeline Parity Project," The Harvard Crimson (December 5, 2018), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/12/5/law-school-womens-groups-boycott-firms/. Notably, though unionizing doesn't appear to have been one of PPP's goals, their speech and activities related to employee mandatory arbitration agreements appear to be protected under Section 7 of the NLRA (see the discussion above). However, speech that crosses into criticizing the client-facing work of the firms may not be protected under the NLRA. See the endnotes accompanying the discussion above under "Why a Law Student Movement is a Promising Path to a BigLaw Union." This distinction is discussed in more detail in part 2 of this article.

[36] https://peoplesparity.org/ourchapters/.

Copyright © 2023-2024 The Sanity Plea LLC

All rights reserved.